In Buddhist philosophy, karma is often misunderstood as a notion of fate or predestination. However, according to the teachings of Kalu Rinpoche, karma is not a rigid law that binds individuals to an unchangeable destiny.

Rather, it represents the fundamental principle that we reap what we sow—our experiences are the direct results of our own actions.

This understanding of karma is deeply intertwined with the concept of dependent origination, known in Tibetan as tendrel. The karmic stream is nothing more than the interplay of interdependent factors, where causes and effects give rise to one another in a continuous and dynamic process.

The Tibetan term tendrel encapsulates the notions of interaction, interconnection, and interdependence. Everything we experience arises through the relationship between interrelated elements. This principle is essential for understanding the Dharma and, in particular, the way the mind transmigrates within cyclic existence (samsara).

To grasp the essence of tendrel, let us consider a simple example. When you hear the sound of a bell, ask yourself: what creates the sound? Is it the body of the bell, the clapper, the hand that moves it, or the ears that perceive it? No single element produces the sound independently; rather, it arises from the simultaneous interaction of all these factors. The sound exists only because of this interplay—this is tendrel.

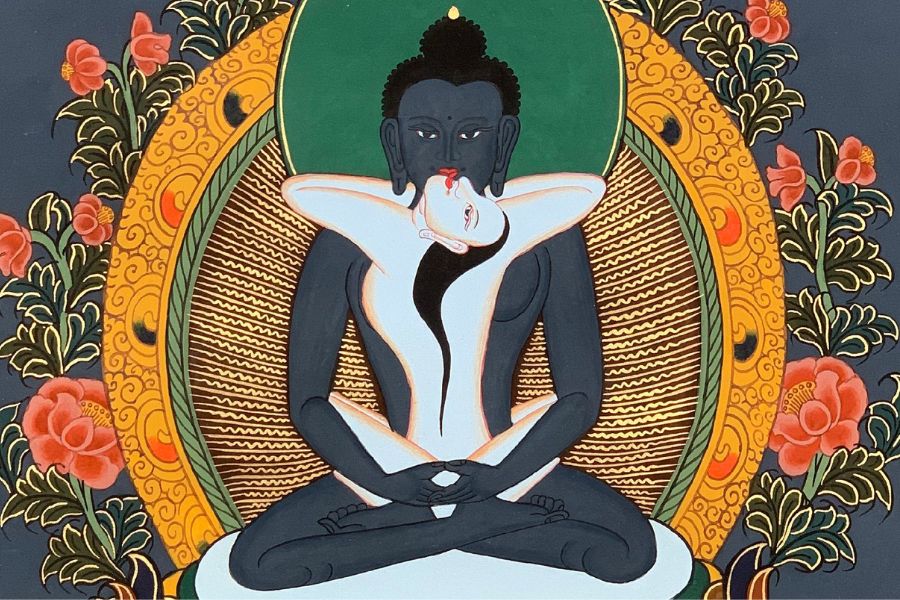

Similarly, all conditioned existence and all manifestations of samsara arise from a complex web of interactions, specifically those described by the twelve links of dependent origination. These twelve factors do not act in a linear sequence but rather coexist, forming an interwoven reality. Just as the sound of the bell depends on multiple elements acting together, the cycle of existence is conditioned by the simultaneous presence of these twelve links.

This interdependent causality creates the illusion of a fixed reality. In truth, everything in samsara is a manifestation of karmically conditioned interrelations. Our experiences, thoughts, and perceptions are all tendrel. This conditioned reality is what Buddhist philosophy refers to as conventional or dualistic truth—an apparent reality shaped by karma. However, at a deeper level, this very interdependence points to the ultimate truth: the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena.

Understanding dependent origination allows us to transcend the limitations of conventional reality and attain true peace and freedom. When one fully realizes tendrel, one also comprehends emptiness—an insight that leads to liberation. This is why it is often said that wisdom is not fundamentally separate from illusion; samsara and nirvana are not two distinct entities but different ways of perceiving the same reality. Ignorance contains the seed of wisdom, just as a rope mistaken for a snake can, upon realization, become a source of understanding.

However, it is crucial to avoid the pitfalls of nihilism. Misinterpreting emptiness as the mere absence of existence can lead to a distorted view that denies the validity of karma, moral responsibility, and the path to awakening. If one were to conclude that everything is void and meaningless, including the Buddha’s realization, such a view would be even more erroneous than believing in the absolute reality of appearances. The Middle Way (Madhyamaka) avoids both extremes—eternalism (believing in an inherent, unchanging reality) and nihilism (denying all existence). This balance enables one to move beyond conceptual fabrications and directly perceive reality as it is.

As the great lineage holder Saraha stated:

"To consider the world as real is a brutal mistake. To consider it unreal is even more deluded."

Similarly, Nagarjuna warned:

"Those who only conceptualize emptiness are beyond help."

Ultimately, the realization of tendrel leads to a profound understanding of the nature of reality—one that liberates the mind from the illusions of samsara and opens the door to enlightenment.