The relationship between attachment and suffering is a recurring theme in J. Krishnamurti's philosophy. He questions the nature of attachment and the constant pursuit of detachment, suggesting that by trying to cultivate detachment, we create a new problem.

But what does he really mean by this? A deeper understanding of attachment leads us to reflect on our motivations and the true obstacles that attachments and fears impose on our inner freedom.

Attachment is a complex human phenomenon that, according to Krishnamurti, is deeply rooted in fear and insecurity. We become attached to people, ideas, possessions, and even to the past. But why is attachment so persistent? It is not only born out of a desire for security but also out of the need for identity. Becoming attached to something is a way of ensuring that our identity, our "self," remains intact in the face of life’s impermanence.

Krishnamurti proposes that attachment arises from the fear of loss and loneliness. When we attach ourselves to something, whether a person, an idea, or a past experience, we are trying to avoid the pain that comes with change or loss. The fear of not being "something," of not being recognized, pushes us into these attachments. And this attachment, no matter how much it tries to provide security, is, in reality, the source of suffering.

In the face of the suffering caused by attachments, many people seek detachment as a form of relief. The idea of being detached seems to offer freedom: freedom from possessions, expectations, and fears. However, as Krishnamurti teaches, when we try to "cultivate" detachment, we are only creating a new form of attachment. The mind becomes occupied with seeking detachment, and thus the conflict between attachment and detachment arises.

This "cultivation" of detachment, therefore, becomes a problem in itself. Instead of alleviating suffering, it reinforces the division between what we are and what we want to be. Detachment becomes a goal, an idea to be achieved, and the mind, in this process, continues to fuel internal conflict. "I am attached, and I must be detached"—this dilemma becomes an endless struggle that generates more suffering.

Krishnamurti suggests that true detachment is not something that can be cultivated or imposed on the mind. Detachment naturally arises when the mind is fully aware of attachment and the suffering it brings, without any judgment or desire for change. True detachment is not an action, but a deep understanding of attachment.

When we become aware of attachment, without rushing to rid ourselves of it, we can delve deeper into its causes. It is not about condemning attachment but observing it with complete clarity. This attentive, non-interfering observation allows the mind to explore attachment in its entirety, understanding its roots, forms, and ultimately, its illusory nature.

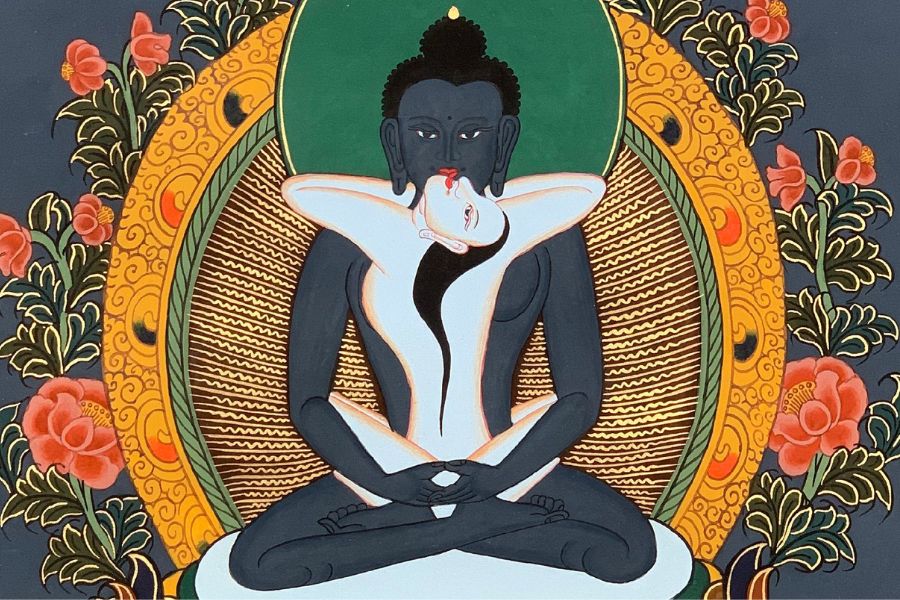

For Krishnamurti, attachment is not synonymous with love. On the contrary, where there is attachment, there is a desire for security and personal continuity, qualities that are incompatible with true love. Love cannot be conditioned by fear or the desire for permanence. Where there is attachment, there is a need to hold on to something, to preserve something, and this prevents the freedom that love requires.

When we view attachment from this perspective, we understand that it is related to fear and the need for control, not to the freedom that love embodies. Detachment, therefore, is not a pursuit of a sterile form of non-attachment, but a deep understanding of what it means to live free from the limitations imposed by our fears and desires.

Instead of trying to escape attachment or cultivate detachment, Krishnamurti invites us to observe our minds with full attention, devoid of any desire or judgment. When the mind is truly vigilant, without expectations, it can perceive the deeper layers of attachment, without becoming consumed by the conflict between attachment and detachment.

This state of full awareness not only dissolves the contradiction between attachment and detachment but also opens up space for a deeper understanding of life. In this state, the mind is no longer at the mercy of ideas or the search for security. By freeing itself from conflict, the mind discovers a genuine freedom, untainted by the suffering that attachment creates.

The problem of attachment is vast and profound. It is not merely a psychological issue but an exploration of the nature of the human mind and how it relates to the world and to itself. Attachment, as Krishnamurti points out, is not something to be "eliminated," but understood. When the mind is truly aware of its own limitations, when it observes attachment without the intent to change it, it begins to discover something completely different – something that is neither attachment nor detachment, but a state of full understanding and freedom.

Therefore, the true challenge is not how to be detached, but how to look deeply into attachment and understand what it reveals about ourselves and our lives. And in doing so, we can discover true freedom, beyond the limitations of attachment and detachment.